The K500 Insider's Guide to choosing an auction

Buyers and sellers – even sophisticated, experienced collectors – are frequently baffled by the choice of auction house and the startling variation in commission rates. Why do premiums vary so wildly between one house and another? Does a higher commission rate mean a better service? When should you consider a private sale?

We clarify the issues, give you the facts and figures, and ask some expert insiders for their views on this complex and contentious issue…

What commission should I expect to pay?

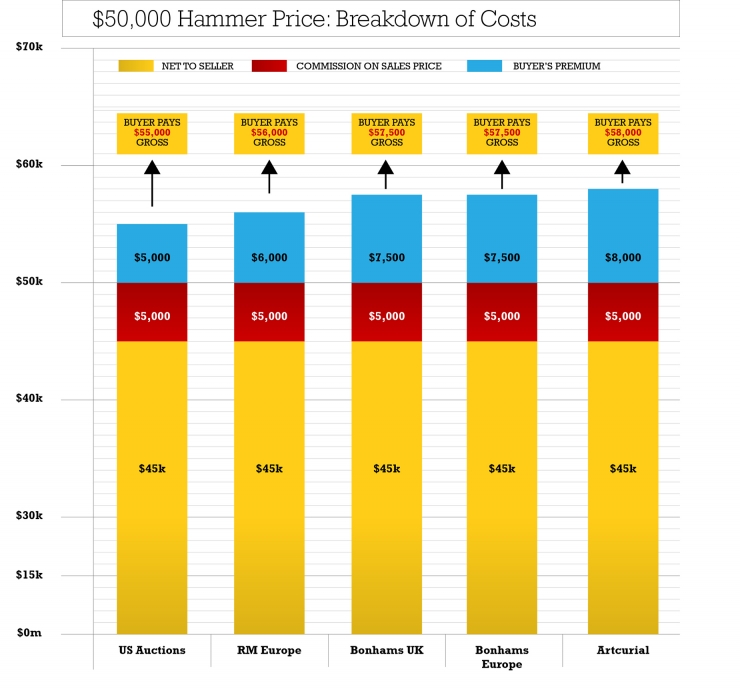

The chart shows the buyers’ premiums charged by the major collectors’ car auctions. These range from 10% to 16% for motor cars – to which VAT or equivalent local tax is added.

Then there’s the sellers’ commission. Generally, the quoted rate is 10% (+ local VAT), although some provincial houses might charge less. So, if the buyers’ premium is 15% and there’s 10% seller’s commission – plus, say, 20% VAT on those two fees – almost a third of the money paid by the buyer never finds its way to the seller. Compare that with estate agents, who typically charge just 3 or 4%, and you’d be right to question what you get for your money.

But I’m selling, so the buyers’ premium is irrelevant to me

“Auction houses, like any business, want to give the impression they’re exceeding customers’ expectations, but remember: estimates are published without premium, and results include it,” says Simon Kidston, who spent almost two decades as an auctioneer. “You’re not comparing like for like. Sellers won’t receive anywhere near the published sale figures, so shouldn’t base their price expectations on them. You’d be amazed how naïve many otherwise very sophisticated and experienced business people can be when it comes to recognising that it’s the combined commission rate – buyers’ plus sellers’ – that they need to consider. What ultimately matters is the difference between what the buyer pays and the seller receives.

“Bizarrely, many sophisticated sellers completely ignore this aspect. An auction house might woo a seller by saying, ‘We’ll do you a great deal on the commission’ or for a ‘trophy’ lot they might even offer to sell the car ‘for free’. The seller often believes that as the buyers’ premium is paid by the buyer, the seller is effectively getting a ‘no cost’ service. But of course they’re not: it all comes out of the same pot. A buyer will take all his or her costs into account and usually bid less if the premium is high, particularly if there are other cars of the type available.”

Are the premiums negotiable?

Former head of RM Europe, Max Girardo, points out: “The buyers’ premium is never negotiable. For a start, it could create a conflict of interest, as the auctioneer might be incentivised to sell a car to the under-bidder if he knew that this would bring the auction house more commission. And to be fair, it simply wouldn’t work to have a roomful of buyers all paying different rates of commission.

“Sellers’ commission is a different matter. If a seller is offering a very special, very valuable car, an auction house should be open to negotiation on the commission.”

So should I calculate the lowest (buyers’ plus sellers’) premium and plump for that?

“Choosing the auction purely on the basis that it offers the lowest combined commission is likely to be a false economy,” warns former Christie’s senior specialist Malcolm Welford. “An auction house could charge the seller zero, but if it doesn’t attract a bidder, it’s of no use to anyone.

“However, some auction houses justify high commissions by claiming they have higher overheads, and in such cases you’d be well advised to assess whether the extra expense is really worth it. What are you getting for the higher fee?

“It’s possible that it’s justified, even as a buyer. For example, some houses help the buyer with travel arrangements and hotels, and really hold their hands through the whole process, which makes them more likely to bid. Others make you question where the extra money is being spent – with the buyers’ premium feeling more like a tax than a cost for which you get something in return. Increasingly, collectors are clamouring for an explanation of where their money is being spent.”

Remember also, that despite charging buyers a commission, legally the auction houses are working for the seller. Their conditions make it clear that they owe little if any duty to the buyer, whose interests are completely opposed to theirs.

“For the seller,” adds ex-Sotheby’s car department boss Martin Chisholm, “there are other considerations. If you have an exceptional automobile that you genuinely believe would appeal to an international collector, then do consider taking the plunge and proposing it for a high-level auction. You will inevitably pay a higher commission. The house might even – if it’s a relatively humble car – insist that it’s sold at No Reserve. But the sale price might make the gamble worthwhile.

“On the other hand, if you have ‘yet another’ V12 E-type or Derby Bentley then it’s worth looking very carefully at the commission. Buyers know more or less what these cars are worth and if the price ventures too high, there’s always another for sale. A top-level auction premium here is often wasted money.”

There’s another point owners of ‘major league’ cars should consider: auction houses don’t need to sell your car to benefit. Its appearance in pre-auction marketing might attract other sellers, whether yours finds a buyer or goes home unsold. And ‘burnt’.

Or should I go for a private sale?

“It depends very much on the car,” says Max Girardo, who recently moved into the private sales arena. “Some cars clearly do better at auction: for example, the Bugatti that was fished out of a lake. The romance of the car’s story and the resulting competition between two bidders drove the car’s price way above what could ever have been achieved privately.”

In a similar vein, Simon Kidston cites the 1956 Fiat Eden Roc beach car with Pinin Farina coachwork (pictured, top), one of only two made, that Gooding offered at Pebble Beach in 2015, quoting ‘No Reserve’ and ‘Refer Dept’: “That in itself is an odd combination, as No Reserve says it’s here to be sold, while Refer Department is auction code for ‘it’s so expensive we’re embarrassed to tell you’”.

In this case, the ‘Refer Dept.’ estimate was a punchy $250,000 – yet Gooding managed to sell the beach car for a staggering $660,000 all-in. “Never in a million years would that car have achieved that amount in a private sale,” says Simon. “The vendor was the Doheny oil dynasty of California. They had bought it new and were obviously sophisticated people, so they decided to put it in a top auction and their gamble was rewarded with a spectacular result.

“But a private sale might be best for something which has a relatively illiquid market, or something extremely high-profile where it wouldn’t necessarily be a plus for the world to know that the owner is selling. A really good dealer should already know the people who are candidates for buying such a car and, of course, private collectors love nothing better than the notion that an opportunity is open to them that is not available to rival collectors. Clearly, an auction can’t achieve that.”

Some thoughts to carry away

• Be aware of both the buyers’ and sellers’ commissions, but don’t make a decision based purely on the cheapest option. Sometimes (but not always) you get what you pay for (‘Our Paris venue is very expensive, which is why we charge a high premium throughout Europe’ does not qualify).

• If an auction house is charging less than anyone else, they’re likely to be spending the least on marketing and on retaining the top staff with the best contacts.

• At the same time, do question extortionate premiums. One house’s two-tier, 16% / 12% commission (plus VAT, which they are alone in including in published results) for buyers has its critics. To counterbalance this, they often negotiate low reserve prices with sellers. Who wins?

• When you’ve calculated how much of what the buyer pays goes to the auction house, not the seller, look carefully at what that house can offer. Look at a) its past performance; b) the quality of its marketing; and c) the calibre of its staff.

• When considering performance, the best indicator is the auction’s ‘sales success’ figures – the percentage sold both by lot and by overall value. K500 alone can give you all these figures.

• One final inside tip: the auction house cares more about your reserve price than what commission you pay. Dangling a low reserve price in return for a low commission rate creates a win-win for both parties.

Use the above barometers to make your decision, but remember that there’s no ‘one size fits all’. It all depends on the car, and what you realistically hope to achieve.

As Simon concludes, “Every auction house has its lucky and unlucky days, but if you consistently go to the house that charges the least, you’re thinking small and the results will be small. If you want big results, you’ll need the auction house with the tools to achieve that.

“See what percentage the auction house is selling, by lot and by value, and then compare that to the commissions they are charging. Ask yourself which ones are actually delivering on their promises.”

Luck, of course, is unpredictable. A final word to the wise? “Never go to auction just to ‘test the market’, only to sell.”

Photos by K500